Dans la conception et la fabrication mécaniques, les filets se trouvent souvent dans une zone grise. Certaines parties sont entièrement dépourvues de congés, avec chaque bord nettement défini, tandis que d'autres présentent des coins arrondis sur presque tous les bords possibles.

Les congés sont bien plus que de simples détails esthétiques : ils peuvent améliorer considérablement les performances mécaniques en réduisant la concentration des contraintes., prévenir les fissures, et améliorer l'ergonomie. Cependant, les congés inutiles peuvent augmenter le temps de programmation CNC, coût d'usinage, et même compliquer le montage.

L'ingénierie des congés comporte deux composants principaux:

Conception de géométrie de congé – Création de la transition arrondie entre deux surfaces dans un modèle CAO.

Usinage de congés – Réalisation du congé dans la pièce physique à l’aide d’outils CNC, le plus souvent une fraise à bout arrondi ou une fraise à boule.

Dans ce guide, nous explorerons quand les filets sont essentiels, quand ils devraient être évités, et comment les concevoir pour des performances et une fabricabilité maximales.

Filets vs. Autres traitements de bord

Les congés sont parfois confondus avec d'autres caractéristiques de conception telles que les chanfreins., rayons d'angle, et biseaux. Alors qu'ils modifient tous les arêtes vives, ils diffèrent par leur géométrie et leur fonction:

Filet – Un lisse, transition courbe entre deux surfaces, défini par un rayon. Peut être interne (concave) ou externe (convexe).

Rayon de coin – Arrondit spécifiquement un externe bord d'une pièce.

Chanfreiner – Un appartement, coupée inclinée (souvent 45°) qui supprime un coin pointu.

Biseau – Une surface en pente s'étendant à partir d'un bord horizontal ou vertical, pas forcément à 45°.

Distinction clé: Les congés ont une vraie courbe de rayon, alors que les chanfreins et les biseaux ne le font pas. Les chanfreins sont souvent préférés pour les fonctions d'assemblage (par exemple., insertion de vis ou de broches), tandis que les filets sont meilleurs pour réduire les concentrations de stress.

Quand les filets doivent être évités

Toutes les pièces ne bénéficient pas des congés. Les ajouter aux mauvais endroits peut augmenter les coûts sans améliorer la fonctionnalité..

3D Pièces imprimées

En fabrication additive, aucun outil n'a besoin d'un dégagement pour découper des éléments, des coins internes si pointus sont tout à fait réalisables. Les congés ne peuvent être nécessaires que dans les conceptions imprimées en 3D pour soulagement du stress dans les zones à forte charge ou pour à des fins esthétiques.

Cependant, si vous envisagez de passer ultérieurement de l'impression 3D à l'usinage CNC, incorporer dès le départ des tailles de filet pouvant être fabriquées pour éviter les coûts de refonte.

Bords inférieurs des cavités et des trous

Filetage des bords inférieurs des poches, murs, ou des trous borgnes nécessitent des trajectoires d'usinage 3D et des fraises à bille, lequel:

Ralentir l’enlèvement de matière par rapport aux fraises plates.

Augmente l’usure des outils et le risque de casse.

Nécessite un temps d’installation et de programmation plus long.

Dans de nombreux cas, la contrainte au fond des trous peut être réduite plus efficacement en changeant profondeur de trou, épaisseur de paroi, ou placement de fonctionnalités — bien moins cher que l'ajout de congés de fond complexes.

Considérations sur l'usinage CNC pour les congés

La taille minimale du congé est limitée par l'outil

Les fraises CNC sont rondes, et ils ne peuvent couper que des courbes aussi petites que leur propre rayon.

Le plus petit outil standard que la plupart des magasins gardent en stock est 1/32" (~0,8 mm de diamètre), ce qui signifie que le plus petit rayon de congé qu'ils peuvent réaliser sans outils spéciaux est à propos 0.4 mm.

Si vous concevez un congé plus petit que cela, le magasin devra peut-être commander un cutter personnalisé, ce qui signifie des délais de livraison plus longs et des coûts plus élevés.

Conseil: Respectez les tailles de coupe courantes pour maintenir les coûts bas et éviter les retards.

La profondeur de coupe affecte la taille du congé

Plus un outil doit atteindre profondément, plus il va fléchir (dévier) et vibrer. Cela limite la profondeur à laquelle une fraise de petit diamètre peut aller sans se casser ou laisser une mauvaise finition..

Voici une règle empirique que la plupart des machinistes suivent:

| Matériel | Profondeur de coupe maximale | Limite de taille de filet équivalente |

| Acier | 5× diamètre de l'outil | 10× rayon du congé |

| Aluminium/plastiques | 10× diamètre de l'outil | 20× rayon du congé |

Exemple: Si vous utilisez un 1 coupe-filet à rayon mm en aluminium, tu peux couper 20 mm de profondeur max avant de rencontrer des problèmes.

Des rayons plus grands sont généralement plus faciles

Les machinistes aiment les filets plus gros car ils leur permettent d'utiliser des filets plus forts., des couteaux plus gros qui enlèvent le matériau plus rapidement et durent plus longtemps.

Un petit rayon peut paraître élégant en CAO, mais cela pourrait doubler le temps d'usinage en réalité.

Évitez les filets cosmétiques inutiles

Si le filet est uniquement pour le look (cosmétique), demandez-vous: est-ce que ça vaut le temps supplémentaire de la machine?

Parfois, il suffit de casser le bord avec un chanfrein rapide ou un petit rayon fait manuellement après l'usinage est plus rapide et moins cher.

Faire correspondre les tailles de congé aux outils standard

Rayons de congé communs - comme 1 mm, 2 mm, 3 mm, 6 mm — correspond aux fraises standards.

Des tailles étranges comme 2.37 mm ça veut dire que le machiniste devra interpoler (fraisez-le en plusieurs passes), ce qui prend plus de temps.

Envisagez des méthodes alternatives

Si vous avez juste besoin d'un bord arrondi pour plus de solidité (comme dans les joints soudés), vous n'aurez peut-être pas du tout besoin de l'usiner CNC.

Soudage d'angle peut créer un joint arrondi une fois les pièces assemblées, sauter complètement l’usinage supplémentaire.

Cas d'utilisation facultatifs pour les congés

Bien que ce ne soit pas toujours nécessaire, les congés peuvent améliorer certains aspects de la conception des pièces.

Bords cosmétiques du visage

Un petit rayon peut rendre les transitions de surface transparentes et améliorer la qualité perçue. Utilisez-les uniquement après avoir finalisé la géométrie fonctionnelle, car ils augmentent le temps d'usinage.

Sécurité et ergonomie

Les pièces aux bords tranchants peuvent provoquer des blessures lors de la manipulation, notamment dans les composants métalliques. Les machinistes « cassent » généralement les bords par défaut, mais si tu as besoin d'un rayon précis pour le confort (par exemple., poignées ergonomiques), précisez-le clairement dans le dessin.

Aide au montage

Les congés peuvent guider les broches, arbres, ou les attaches en place, mais les chanfreins sont généralement préférés pour les pièces à accoupler car elles offrent une meilleure entrée sans ajouter de coût significatif.

Quand les filets sont nécessaires

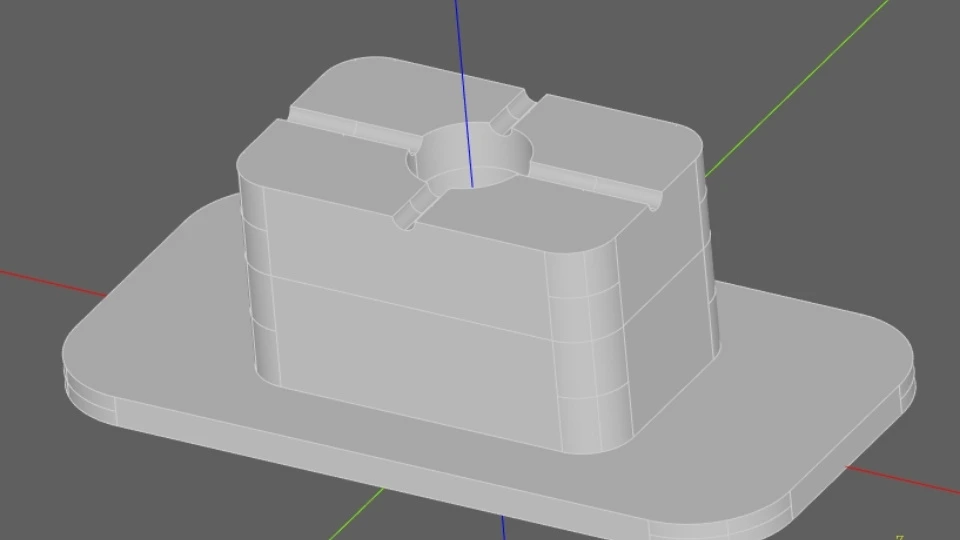

Coins intérieurs entre deux murs verticaux

Les outils de coupe CNC sont ronds, ils ne peuvent donc pas créer un coin intérieur parfaitement net à 90°.

Si votre conception comporte deux murs verticaux se rejoignant dans un coin intérieur, toi avoir pour ajouter un congé qui correspond (ou est plus grand que) le rayon de l'outil de coupe.

Pourquoi? Sans le filet, l'outil laisserait du matériel supplémentaire dans le coin, et votre pièce ne s'adapterait pas à ses pièces correspondantes.

Exemple: Pensez à une pochette carrée dans une plaque métallique : les coins seront toujours légèrement arrondis car la fraise est ronde.

Bords internes entre des surfaces inclinées ou courbes

Lorsque deux surfaces inclinées ou courbes se rencontrent, surtout dans les formes organiques ou de forme libre, ils sont généralement usinés avec une fraise à boule.

Le plus petit congé que vous pourrez y avoir sera le rayon de cette fraise sphérique..

Pourquoi? Si vous essayez de rendre la courbe plus serrée que le rayon de l'outil, le coupeur ne peut tout simplement pas atteindre le coin sans laisser de matériau non coupé.

Exemple: Sur une pièce de moteur de voiture avec écoulement, surfaces sculptées, toutes les transitions internes entre les courbes auront des congés intégrés basés sur la taille de l'outil.

Où un mur vertical rencontre une surface inclinée ou incurvée

Celui-ci est un peu plus difficile à visualiser : imaginez un grand mur vertical, et à sa base, au lieu d'un sol plat, il y a une pente ou une courbe.

Si vous essayez de couper le mur et la courbe sans congé, le coupeur laissera une petite bande de matériau non coupé juste à la jonction.

L'ajout d'un congé ici assure une transition en douceur et évite les restes de matière.

Exemple: Dans une empreinte de moule pour une pièce en plastique, la transition d'un côté vertical à une base incurvée comporte presque toujours un congé pour que le couteau puisse se déplacer librement.

Avantages techniques des congés

Ils réduisent l'accumulation de stress

Les angles vifs agissent comme des aimants de contrainte — lorsqu'une pièce est sous charge, la force se concentre sur ce bord tranchant, ce qui peut entraîner des fissures.

Un filet s'étale qui ressort en douceur, afin que la pièce puisse supporter plus de charge sans se casser.

Exemple: Pensez à plier un morceau de métal : il se fissure presque toujours au niveau du pli prononcé., pas au milieu. Une courbe douce résout ce problème.

Ils aident les pièces à durer plus longtemps

Dans les pièces soumises à des chargements et déchargements répétés (comme des bras de machine ou des supports), les coins pointus peuvent provoquer des fissures de fatigue au fil du temps.

Les filets réduisent cet « effet de fatigue »," ce qui signifie que vos pièces durent plus de cycles avant de s'user.

Exemple: Les composants d'avion ont presque toujours des congés dans les zones à fortes contraintes pour éviter les ruptures par fatigue.

Ils rendent les pièces plus sûres à manipuler

Si votre pièce sera touchée ou assemblée par des personnes, les coins pointus peuvent couper les mains ou accrocher les vêtements.

Un congé supprime cette arête vive et rend la pièce plus confortable et plus sûre à travailler..

Exemple: Poignées, couvertures, et les panneaux de commande ont souvent des filets généreux pour qu'ils soient doux dans votre main.

Ils peuvent améliorer le flux

Dans les conceptions où les liquides ou l'air se déplacent dans un coin, les arêtes vives peuvent provoquer des turbulences ou bloquer l’écoulement.

Un congé permet au fluide de changer de direction plus facilement, Amélioration de l'efficacité.

Exemple: Dans les systèmes de tuyauterie, les filets internes réduisent la chute de pression et améliorent le mouvement du fluide.

Ils ont l'air mieux

Un bord arrondi et lisse donne souvent à un produit un aspect plus « fini » et professionnel.

Bien qu'il s'agisse plus d'une question d'esthétique que de fonction, cela peut être important pour les produits destinés aux consommateurs.

Exemple: Les coins arrondis de votre smartphone ne sont pas seulement destinés au confort : ils donnent également à l'appareil un aspect élégant..

Ils peuvent faciliter l'usinage

En usinage CNC, certains coins internes pointus ne peuvent tout simplement pas être coupés car les outils sont ronds.

En ajoutant un congé, vous concevez la pièce d'une manière qui correspond à la forme de l'outil, ce qui peut rendre l'usinage plus rapide et moins cher.

Faits clés sur les filets

Un congé n'est qu'un bord arrondi

À la base, un congé arrondit simplement un coin pointu où deux surfaces se rencontrent.

Cela peut être à l'intérieur un coin (concave) ou dehors sur un bord (convexe).

Exemple: La courbe intérieure où la lame rencontre le manche d'un couteau de cuisine est un filet interne.

Les outils CNC réalisent des filets avec des couteaux spéciaux

La plupart des congés CNC sont réalisés à l'aide d'un outil d'arrondi de coin ou un fraise à boule.

Ces outils sont façonnés pour laisser naturellement une courbe douce lors de la coupe., vous obtenez donc un rayon constant à chaque fois.

Les congés sont courbés, Les chanfreins sont plats

C'est facile de les mélanger, mais la différence est simple: différence dans les détails du congé et du chanfrein

Filet = courbe

Chanfreiner = angle plat

Si tu passes ton doigt sur le bord, un filet est lisse et arrondi, tandis qu'un chanfrein ressemble à une pente droite.

Les filets sont meilleurs pour soulager le stress

Lorsqu'une pièce est sous pression ou pliée, les angles vifs peuvent créer des « points chauds » de contrainte qui peuvent se fissurer avec le temps.

Les congés adoucissent la transition et répartissent cette contrainte sur une plus grande surface, rendre la pièce plus solide.

Exemple: C'est pourquoi les coins des fenêtres des avions sont arrondis : les coins pointus se fissureraient sous les cycles de pression de l'air..

Ils n'ajoutent pas beaucoup de matériel, Mais ils ajoutent beaucoup de force

L'ajout d'un congé modifie à peine la surface de la section transversale de la pièce., mais cela peut réduire considérablement la concentration du stress.

Cela signifie que vous pouvez améliorer la résistance et la durabilité sans rendre la pièce plus lourde ou plus volumineuse.

Ils peuvent économiser ou vous coûter de l'argent

Si un congé correspond à une taille d'outil standard, cela peut en fait faciliter l'usinage.

Mais s’il s’agit d’une taille inhabituelle ou dans un endroit difficile, cela peut augmenter le temps et le coût d'usinage.

Le truc c'est de savoir où pour les mettre et quelle taille pour les faire.

Conclusion

Filets dans Usinage CNC sont des fonctionnalités de conception puissantes, mais uniquement lorsqu'elles sont utilisées de manière stratégique. Par compréhension quand ils sont requis, quand ils peuvent être ignorés, et comment les dimensionner de manière appropriée, vous pouvez réduire les coûts d'usinage, améliorer les performances des pièces, et simplifier la fabrication.

En cas de doute, consultez votre partenaire d'usinage dès le début du processus de conception. Des filets bien planifiés peuvent faire la différence entre un projet coûteux, pièce trop compliquée et optimisée, conception réalisable.

FAQ

1. What is the fundamental difference in function between a Fillet and a Chamfer?

The difference lies in geometry and stress relief:

-

Filet: UN curved transition (défini par un rayon, R.). Its primary function is soulagement du stress by smoothly distributing force away from sharp corners, which is critical for parts under dynamic or fatigue loading.

-

Chanfreiner: UN plat, coupée inclinée (généralement 45°). Its primary function is to break a sharp edge for safety and assembly ease (providing lead-in for pins or screws), but it is less effective than a fillet for stress concentration reduction.

2. Why can’t a standard square end mill create a perfect 90° internal corner?

A standard end mill has a round circumference. When it cuts, the center of the tool can reach the corner intersection, but the radius of the tool cannot; it always leaves a small amount of material behind, creating a rounded internal corner. Donc, every internal corner in a pocket or slot machined with a standard end mill must have a radius equal to or larger than the radius of the cutting tool used.

3. What is the rule of thumb for designing the minimum internal fillet size for CNC machining?

The fillet radius (R.) must be equal to or slightly larger than the radius of the smallest end mill that can reach the feature. A common industry standard is to design the fillet radius R. to be 1.2 X tool radius ou 0.6 X tool diameter. This small buffer helps ensure the tool can move smoothly without being overstressed, and it allows the use of standard, off-the-shelf cutters, which keeps costs down.

4. Why do unnecessarily large or odd-sized fillets increase machining costs?

-

Large Fillets: Require the use of a very large tool or multiple passes with a smaller tool, increasing machine time.

-

Odd-Sized Fillets (par exemple., R2.37 mm): Force the machinist to use interpolation (cutting the curve with multiple short linear passes) rather than using a standard outil d'arrondi de coin. Interpolation takes longer and is more complex to program than simply using a tool that already matches a standard size (par exemple., R3 mm).

5. What does the ratio of “Max Cutting Depth” to “Tool Diameter” indicate for fillets?

This ratio relates to the tool’s aspect ratio et rigidité. The deeper a tool must reach to cut a fillet, the longer its stick-out and the greater the risk of tool deflection and vibration. The article suggests rough guidelines (par exemple., 5 X tool diameter for steel) to limit the depth a small-diameter cutter can safely reach without breaking, pliant, or creating a poor finish due to chatter.

6. When is it better to use a Chamfer instead of a Fillet for assembly assistance?

UN Chanfreiner is generally preferred when the goal is to provide a smooth introduction for a mating part, such as a pin, shaft, or fastener. Chamfers are faster and cheaper to machine than fillets and are highly effective at guiding components during assembly because the flat, angled surface directs the mating piece to the center more precisely than a full curve.

7. What are the key engineering benefits of adding fillets in high-stress areas?

The key benefit is the reduction of Concentration de contraintes. Sharp internal corners act as stress risers, where external loads are amplified, leading to localized failure. A fillet smoothly transitions the load across a larger area, reducing the peak stress and significantly increasing the part’s Vie de fatigue et ultimate strength. This is vital for brackets, load-bearing arms, and anything subjected to cyclic loading.