Thin walls are an unavoidable design requirement in modern manufacturing, driven by the imperative to reduce material consumption, lower weight, and achieve sleek, compact form factors. While conventional wisdom might suggest thickening walls to solve molding headaches like short shots, warpage, or surface defects, this option is often restricted by functional, aesthetic, or cost constraints.

Thin Wall Injection Molding (TWIM) is a specialized process that leverages advanced materials, high-speed machinery, and precision tooling to successfully produce parts where the flow length-to-wall thickness ratio (L/t) is extremely high. This guide walks through the critical technical aspects of TWIM, covering design principles, material selection, processing parameters, troubleshooting, and real industry applications, ensuring parts can be moved confidently into high-volume production.

Defining Thin Wall Injection Molding (TWIM)

There is no single universal cutoff for what constitutes a “thin wall.” The determination depends on a complex interplay of the material’s rheology, the part’s geometry, and the capability of the molding machine.

For instance, a $1.0 \text{ mm}$ wall made from highly flowable Polypropylene (PP) might fill effortlessly, whereas the same wall thickness in high-viscosity Polycarbonate (PC) could result in chronic short shots. Similarly, a small, simple cup with a $1.5 \text{ mm}$ wall is easily molded, but a long, complex housing with intricate ribbing may struggle even with a $2.0 \text{ mm}$ wall.

In practice, most engineers rely on two benchmarks:

Strict Definition: Wall thicknesses $\le 1.0 \text{ mm}$ (0.04 in.).

Broader Definition: Wall thicknesses up to $2.0 \text{ mm}$ (0.08 in.), particularly for larger parts or parts made with low-flow engineering resins.

The Core Defining Factor: High L/t Ratio

What truly defines thin-wall molding is the Flow Length-to-Wall Thickness Ratio (L/t). This ratio measures the distance the molten plastic must travel relative to the cross-sectional area of the flow path. Once this ratio climbs above $\mathbf{150:1}$, the process demands substantially higher injection speeds, greater clamp tonnage, and tighter thermal control compared to conventional molding.

Thin Wall vs. Conventional Injection Molding

| Feature / Requirement | Thin Wall Molding (TWIM) | Conventional Molding |

| Typical Wall Thickness | $\le 1.0 \text{–} 2.0 \text{ mm}$ | $2.5 \text{–} 4.0 \text{ mm}$ or more |

| Flow Length-to-Thickness Ratio (L/t) | $\mathbf{150:1}$ or higher | $100:1$ or lower |

| Injection Speed | $\mathbf{300 \text{–} 600 \text{ mm/s}}$ (Requires High-Speed Machines) | $50 \text{–} 150 \text{ mm/s}$ (Standard Hydraulic) |

| Clamping Force | Higher (Requires high tonnage to resist peak cavity pressure) | Lower (Standard tonnage sufficient) |

| Cycle Time | $\mathbf{3 \text{–} 6}$ seconds (Shorter due to rapid cooling) | $8 \text{–} 15$ seconds |

| Cooling Control | Very tight, uniform temperature control is mandatory | Less demanding, wider tolerance |

| Typical Applications | Packaging, Medical Disposables, Electronics Housings | Automotive, Appliances, General Parts |

In essence, TWIM is not merely about thin walls; it is a high-speed, high-pressure process dictated by the need to fill the cavity before the melt freezes.

Material Selection for Thin Wall Parts

The choice of resin is perhaps the most critical determinant of success in TWIM, as flowability, stiffness, and heat resistance directly influence process feasibility.

High-Flow Resins (Commodity)

These materials are the staple of TWIM, particularly for parts requiring wall thicknesses below $1.0 \text{ mm}$.

Polypropylene (PP): Possesses excellent rheological properties (low viscosity melt), making it the primary choice for food packaging, caps, and containers. It offers a balance of flow and medium impact resistance.

Polystyrene (PS): Offers similarly excellent flow and superior clarity, making it suitable for clear housings or disposable labware, though its lower toughness limits applications.

Engineering and High-Heat Resins

When mechanical performance or thermal stability cannot be compromised, engineers must turn to less flowable, higher-viscosity materials.

Polycarbonate (PC): Provides high stiffness and exceptional impact strength, ideal for electronics housings and safety parts. However, its higher melt viscosity requires significantly faster injection speeds and higher pressures to fill thin sections consistently.

Polyetherimide (PEI – Ultem): Used for aerospace or medical applications requiring high service temperatures ($\text{up to } \sim 170^\circ \text{C}$). Molding PEI in thin walls demands robust, powerful machines and extremely high, carefully managed mold and melt temperatures.

| Property / Material | Polypropylene (PP) | Polystyrene (PS) | Polycarbonate (PC) | Polyetherimide (PEI) |

| Flowability | Excellent | Excellent | Fair to Poor | Fair |

| Stiffness | Medium | Low to Medium | High | Very High |

| Heat Resistance | Up to $\sim 100^\circ \text{C}$ | Up to $\sim 90^\circ \text{C}$ | Up to $\sim 120^\circ \text{C}$ | Up to $\sim 170^\circ \text{C}$ |

| TW Feasibility | Common | Good | Limited (requires power) | Possible (requires powerful machines) |

Mold Design Principles for Thin Wall Injection Molding

Mold design is where the process is truly enabled, as the tool must handle high cavity pressures, rapid filling, and intensive thermal cycling.

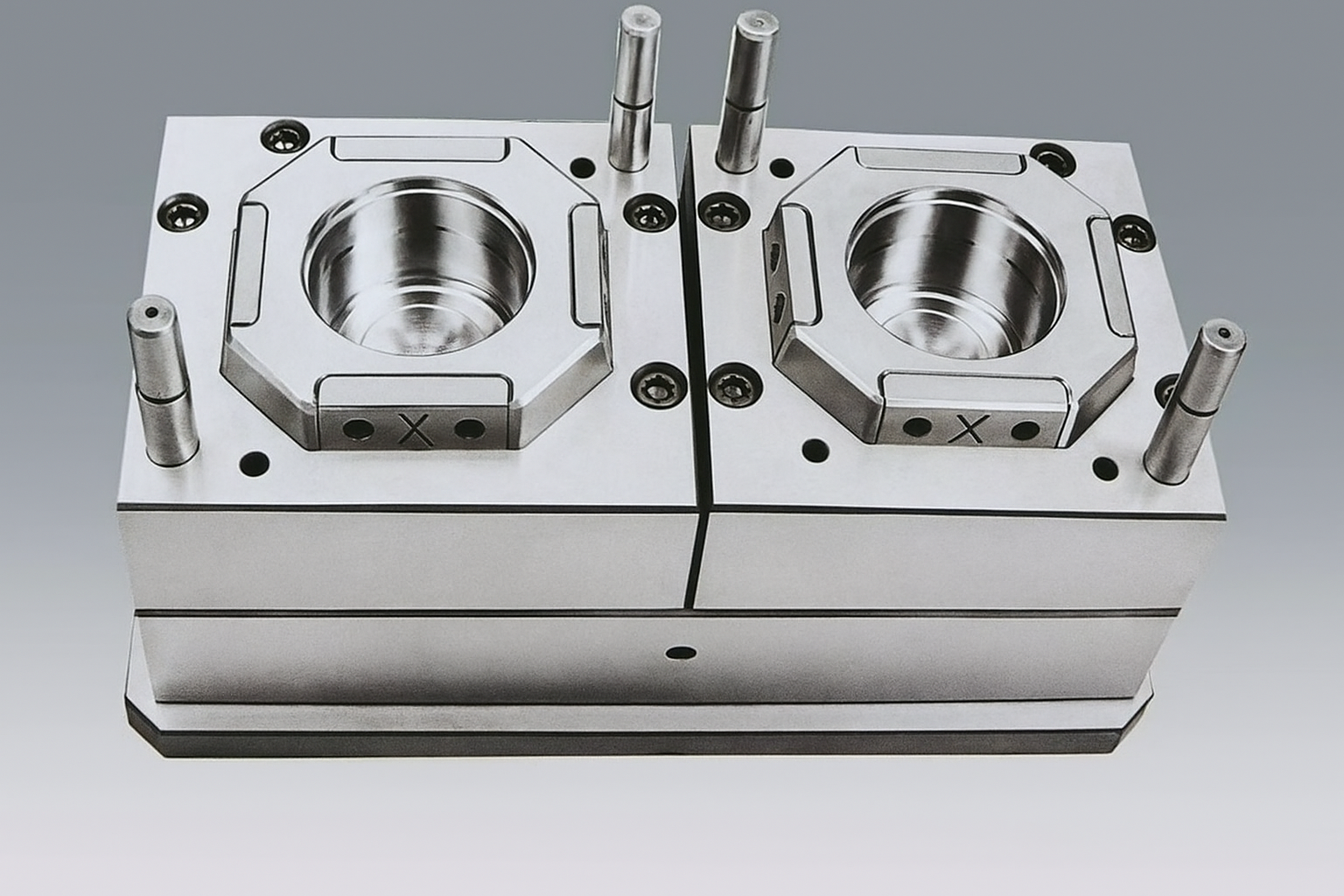

1. Mold Steel and Durability

TWIM requires hardened tool steels, such as H13 or S7, over softer grades. The combination of high injection pressures ($\mathbf{\sim 150 \text{–} 200 \text{ MPa}}$) and the constant, rapid thermal load of fast cycles necessitates a highly durable tool to prevent premature wear, erosion, and deflection.

2. Gate and Runner Design

The runner system must minimize pressure loss and deliver melt to the cavity as fast and uniformly as possible.

Hot Runner Systems: These are strongly preferred, as they eliminate the runner mass and maintain melt temperature right up to the gate, reducing the required injection pressure and improving cycle time.

Runner Cross-Sections: Should be wider and more streamlined than conventional runners to minimize shear heating and flow restriction.

Gating: Valve gates and edge gates are common. Valve gates offer precise, mechanical shutoff, which is vital for preventing stringing and achieving a clean, low-vestige gate mark. Gates are often positioned to shorten the flow path and ensure flow fronts meet in non-critical areas.

3. Venting and Cooling

Since thin sections solidify in milliseconds, air entrapment and uneven cooling are immediate threats.

Venting: Poor venting leads directly to short shots (pressure lock) or burn marks (adiabatic compression). Mold designers must utilize aggressive venting strategies, including vents at the parting line, micro-vents near the end-of-fill areas, and sometimes vacuum assist.

Cooling: Uniformity is paramount to prevent warpage. Cooling channels must be closely spaced and highly efficient. Conformal cooling (3D printed mold inserts that follow the contour of the cavity) is increasingly used to maintain precise thermal balance across the mold surface, which drastically reduces cycle time while maintaining dimensional accuracy.

Processing Parameters and Machine Requirements

Success in TWIM relies on the ability of the machine and operator to precisely manage extremely high power inputs in a fraction of a second.

1. High-Speed Injection Machines

Thin walls freeze so quickly that the injection must occur at high speed to overcome the rapid viscosity increase.

Injection Velocity: Machines must be capable of sustained injection speeds typically between $\mathbf{300 \text{ mm/s} \text{ and } 600 \text{ mm/s}}$.

Equipment: All-electric or hybrid presses are dominant because they can deliver and repeat these high injection velocities with superior precision and acceleration compared to standard hydraulic machines.

2. Critical Processing Parameters

Melt Temperature: Must be optimized—hot enough to maintain low viscosity for fast flow, but not so hot as to cause thermal degradation or excessive cooling time.

Injection Speed and Pressure: Injection speed is the control variable used to achieve the desired fill time (often $<0.5$ seconds). Injection pressure is the necessary force, often peaking $\mathbf{2 \text{–} 3}$ times higher than conventional molding, required to sustain that speed.

Holding (Packing) Pressure: The phase is short, but the high pressure must be delivered accurately to compensate for rapid volumetric shrinkage and prevent sink marks or voids.

Mold Temperature: Requires PID control to maintain strict uniformity. Uneven mold temperatures are the primary cause of warpage in thin-walled parts.

| Resin | Melt Temp (∘C) | Mold Temp (∘C) | Injection Speed | Notes |

| Polypropylene (PP) | $200 \text{–} 250$ | $20 \text{–} 50$ | Very High ($\mathbf{300 \text{–} 600 \text{ mm/s}}$) | Excellent flow, common for packaging. |

| Polystyrene (PS) | $180 \text{–} 240$ | $20 \text{–} 40$ | High ($250 \text{–} 500 \text{ mm/s}$) | Good clarity, sensitive to shear heating. |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | $260 \text{–} 310$ | $80 \text{–} 120$ | Medium–High ($200 \text{–} 400 \text{ mm/s}$) | Stiff, requires higher mold temperature and powerful machine. |

| PEI (Ultem) | $340 \text{–} 400$ | $140 \text{–} 180$ | Medium ($150 \text{–} 300 \text{ mm/s}$) | High-heat performance, requires precise thermal management. |

Common Defects in Thin Wall Parts and Solutions

TWIM operates at the limit of the material and process window, leading to predictable, recurring defects often tied to flow, cooling, or pressure imbalance.

1. Short Shots

Root Cause: The molten plastic’s viscosity increases too rapidly as it cools in the thin section, solidifying before the cavity is fully filled.

Typical Fixes: Increase injection speed (to reduce fill time), raise melt temperature, optimize gate location for shorter flow path, or switch to a higher-Melt Flow Index (MFI) resin.

2. Warpage

Root Cause: Internal stress caused by highly differential cooling rates across the part (e.g., one side cooling faster than the other) or non-uniform flow patterns.

Typical Fixes: Balance cooling channels (use conformal cooling), ensure uniform mold temperature control, or slightly reduce peak injection pressure to lower locked-in molecular stress.

3. Weld Lines

Root Cause: Two flow fronts meet, but the plastic is too cool or trapped air is present, preventing proper molecular inter-diffusion and fusion. This results in a weak, visible seam.

Typical Fixes: Increase melt temperature or injection speed (to increase the temperature of the flow fronts at the merge point), optimize gate placement to move the weld line to a non-critical area, and ensure adequate venting at the point where the fronts meet.

4. Sink Marks

Root Cause: Non-uniform cooling in areas with thickness transitions (e.g., thick ribs attached to thin walls). The slower-cooling thick section shrinks after the surface has solidified, pulling the surface inward.

Typical Fixes: Improve wall uniformity (ideal fix), extend the duration or magnitude of the holding (packing) pressure to feed material to the shrinking area, or reduce the thickness of the attached features (ribs).

| Defect | Root Cause | Typical Fixes |

| Short Shots | Thin walls freeze before filling | Raise injection speed/temperature, add gates, use high-flow resin. |

| Warpage | Uneven cooling, residual stress | Balance cooling, adjust mold temp, reduce pressure. |

| Weld Lines | Cold flow fronts, poor venting | Raise melt temp, optimize gates, add vents. |

| Sink Marks | Thick-to-thin transitions, low pack | Improve wall uniformity, extend pack pressure, redesign ribs. |

Applications and Industry Use Cases

TWIM is the standard practice across high-volume, cost-sensitive, and design-intensive industries.

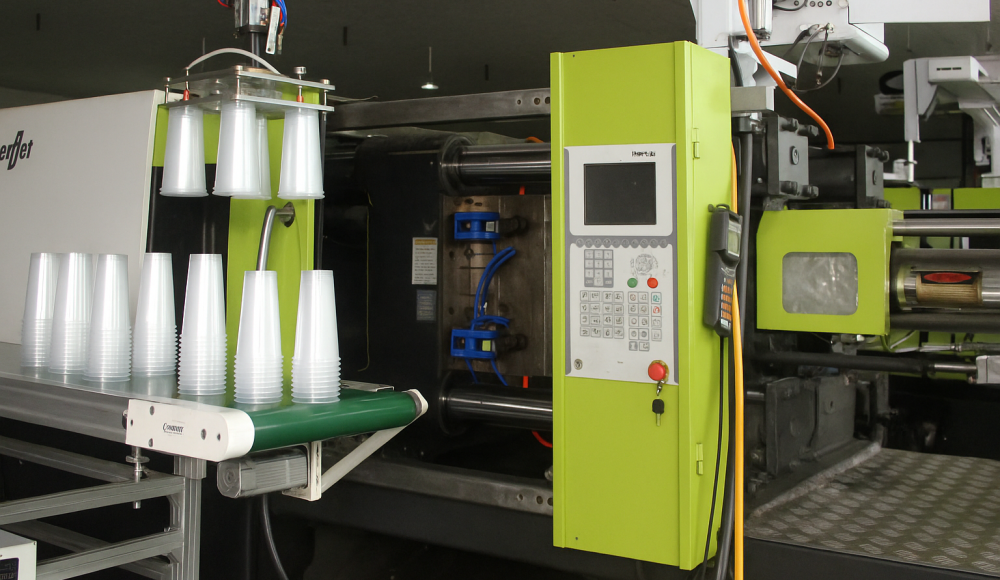

Packaging: This is the highest volume application. Switching from a $2.5 \text{ mm}$ wall to $1.0 \text{ mm}$ can yield up to $20\%$ material savings per part, translating into massive annual cost reductions and sustainability improvements. Products include yogurt containers, lids, and cutlery.

Medical: Used for disposable, single-use components like syringes, diagnostic cartridges, and IV connectors. The process ensures high-speed production of lightweight, sterile parts, often using optically clear resins like PS or COP.

Consumer Electronics: Essential for achieving the minimal thickness required by modern smartphones, laptops, and wearables. TWIM enables the creation of slim, cosmetic-grade enclosures that also support internal thermal management requirements.

Industrial and Automotive: The ability to mold large, thin panels is crucial for vehicle lightweighting (interior trims, instrument panels) to meet stricter fuel efficiency and emission targets.

FAQs

Q1: Why is the Flow Length-to-Thickness (L/t) Ratio the primary metric for defining TWIM?

A: The L/t ratio quantifies the difficulty of the mold-filling process. A high ratio (above $\mathbf{150:1}$) indicates that the molten plastic must travel a long distance through a very narrow channel. This severely limits the time available for injection before the plastic freezes, demanding the extreme speeds and pressures characteristic of TWIM. In contrast, a low L/t ratio allows for more conventional molding parameters.

Q2: Why are All-Electric Injection Molding machines preferred over Hydraulic machines for TWIM?

A: All-electric presses offer superior precision and acceleration. Hydraulic systems struggle to maintain the extremely high, repeatable injection velocities ($\mathbf{300 \text{–} 600 \text{ mm/s}}$) required to fill thin cavities quickly. Electric machines use servo motors for each axis, providing exceptional control over speed, pressure, and positioning, which is critical for maintaining the narrow process window of TWIM.

Q3: What is the role of Shear Heating in TWIM, and is it always a benefit?

A: Shear heating occurs when the plastic melt is forced through small gates and thin walls at extremely high speeds, generating friction and heat. In TWIM, this added heat can be beneficial as it temporarily lowers the melt viscosity, aiding flow and preventing premature freezing. However, excessive shear heating can lead to material degradation, discoloration, and increased internal stress in the finished part, necessitating careful control over injection speed and gate size.

Q4: What is Conformal Cooling, and why is it essential for minimizing warpage in thin-wall parts?

A: Conformal cooling involves creating cooling channels within the mold that closely follow (are ‘conformal’ to) the part’s geometry. Unlike straight-drilled channels, this approach ensures highly uniform temperature extraction across the entire cavity surface. Since warpage in TWIM is primarily caused by differential cooling rates, conformal cooling is essential for rapidly and consistently stabilizing the part’s temperature, minimizing internal stress, and maintaining dimensional accuracy.

Q5: What is the primary purpose of the Holding (Packing) Pressure phase in thin wall molding?

A: The holding pressure phase serves two main goals: compensating for material shrinkage and transferring heat out of the cavity. Because the part solidifies rapidly in TWIM, the holding pressure must be delivered quickly and accurately after the fill phase to pack additional material into the cavity. This action minimizes volumetric shrinkage, which prevents sink marks and ensures the part achieves its intended dimensions and surface finish.

Q6: How deep should vents be in a thin wall mold, and where are they most critical?

A: Vents must be shallow enough to prevent plastic from flowing out (flash) but deep enough to allow air and gas to escape. The accepted depth range is typically $\mathbf{0.01 \text{ mm} \text{ to } 0.03 \text{ mm}}$ (or $0.0005 \text{ in} \text{ to } 0.001 \text{ in}$). They are most critical at the end-of-fill areas and near weld lines, where the flow fronts meet and trapped air is concentrated.

Q7: How can TWIM be cost-effective if initial tooling costs are significantly higher?

A: The cost savings come from two main areas:

Material Savings: Thin walls require significantly less resin per part, leading to massive material cost reduction over the part’s lifespan.

Cycle Time Reduction: TWIM enables extremely short cycle times (often $\mathbf{3 \text{–} 6}$ seconds) due to rapid cooling and fast injection. This drastically increases output volume per hour, quickly amortizing the higher upfront investment in specialized tooling and high-speed machinery.

Conclusion and Partner Selection

Thin wall injection molding is a powerful technology that delivers lighter, faster, and more cost-efficient products without sacrificing performance or aesthetics. It achieves this by capitalizing on reduced material use and significantly shortened cycle times.

However, TWIM is fundamentally less forgiving than conventional molding. The narrow processing window means that high upfront investment in tooling and machinery is mandatory.

Selecting the Right TWIM Partner

Choosing a supplier is a technical decision, not just a price comparison. A successful partner must demonstrate expertise in high-speed, high-pressure management.

| Requirement | Why It Matters | What to Look For in a Supplier |

| High-Speed Presses | Ensures thin walls fill before melt freezes | Electric or hybrid presses capable of $\mathbf{\ge 300 \text{ mm/s}}$ sustained injection speed. |

| Moldflow / Simulation | Predicts and eliminates risks (short shots, warpage) pre-tooling | Access to software like Autodesk Moldflow or Sigmasoft. |

| Advanced Tooling Expertise | Critical for effective venting, gating, and cooling strategies | In-house tool shop or proven long-term partnership with specialized tooling vendors. |

| Experience with Similar Parts | Proves real-world capability under high-stress conditions | Case studies, Cpk data, and reference parts from similar thin wall projects. |

If lightweighting, material efficiency, or high-volume output are priorities for your project, mastering the principles of thin wall injection molding is essential. Partnering with a supplier that possesses the correct blend of design, equipment, and process tuning capabilities will ensure a smooth, cost-effective transition from design to mass production.