The global plastics market, valued near 593 billion USD, relies on efficient and reliable assembly techniques to transform small pellets and pre-formed components into large, finished products like automotive parts, consumer electronics, and medical devices. While injection molding creates monolithic parts, the manufacturing of complex assemblies often necessitates joining two or more plastic pieces.

This guide explores the nine primary methods manufacturers use to join plastic, comparing four welding techniques, three advanced bonding and molding processes, and two simple mechanical/chemical methods, with a special focus on the integrating capabilities of overmolding.

4 Plastic Joining Welding Methods (Friction and Conduction Based)

Plastic welding methods rely on melting the material at the joint interface through friction or conduction, followed by applying pressure to fuse the parts.

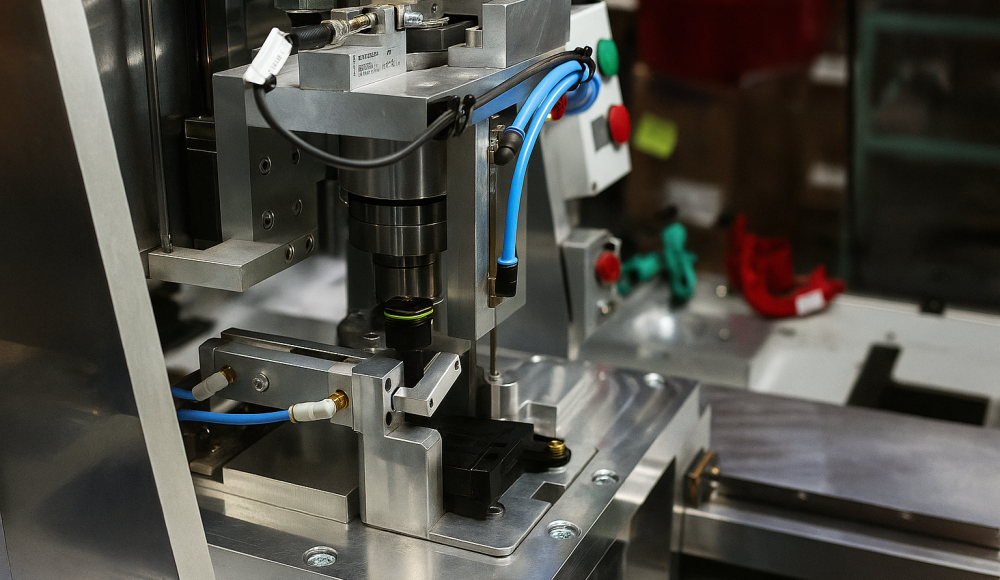

A. Ultrasonic Welding

Mechanism: This process applies high-frequency acoustic vibrations (typically 20 to 40 kHz) to plastic components held together under pressure. The vibrations create intense molecular and interfacial friction within a focused joint design (often using energy directors). This friction rapidly generates heat, melting the thermoplastic material in seconds, allowing the parts to fuse before the vibration stops and the plastic re-solidifies under clamping force.

Key Feature: Speed and versatility. It can also be used for staking or inserting metal components (like threaded inserts) into plastic.

Pros: Extremely quick cycle times (high production rates), results in solid bond strength and hermetic (airtight) seals, requires no consumables or added materials.

Cons: Restricted to specific, rigid thermoplastics, requires significant initial hardware investment, joint design must be precise to focus energy effectively.

B. Spin Welding (Rotational Friction)

Mechanism: Used exclusively for parts with a circular or cylindrical interface. One part is held stationary while the other is spun at high speed (axially symmetric rotation). The continuous friction between the two surfaces generates enough heat to melt the plastic interface. Once the required melt depth is achieved, rotation stops, and the parts are forced together under pressure to create a strong, circular welding joint.

Pros: Practical and repeatable cycle, effective at joining certain dissimilar plastics, excellent joint strength.

Cons: Restricted strictly to circular or tube-shaped joints, limited design flexibility, potential for flash (excess material) and surface finish issues around the weld line.

C. Vibration Welding (Linear Friction)

Mechanism: Similar to spin welding, but uses linear, back-and-forth movement. Two components are clamped, and one part oscillates relative to the other under pressure. This linear friction generates heat at the interface, creating a molten layer that fuses the parts when the movement stops.

Key Feature: Ideal for joining large, irregular, or three-dimensional contoured parts, which cannot be rotated.

Pros: High bond strength, compatibility with a wide variety of thermoplastic types, excellent joint design flexibility (compared to spin welding).

Cons: Slower cycle time than ultrasonic welding, requires high initial equipment cost, restricted to parts with relatively flat or slightly curved joint surfaces.

D. Hot Plate Welding (Conduction Heating)

Mechanism: The joint surfaces of both plastic components are simultaneously melted by pressing them against a temperature-controlled heated plate (platen). Once the required material melt depth is reached, the plate is quickly removed, and the two molten interfaces are immediately pressed together to fuse and cool, creating a permanent bond.

Key Feature: Capable of producing the strongest, most consistent, and most durable hermetic seals among welding methods.

Pros: Highly strong joint creation, compatible with the broadest range of thermoplastics, relatively savvy/cost-effective process compared to laser or ultrasonic systems.

Cons: Slowest of the welding methods (due to heating and cooling time), restricted to flat or slightly bent surfaces, potential for material degradation if temperature is too high.

3 Advanced Plastic Joining Methods (Indirect Heat and Molding)

These methods offer enhanced precision, cleanliness, or integration into the primary fabrication process.

A. Infrared Welding

Mechanism: This is a non-contact process. Intense infrared (IR) beams are focused onto the joint interfaces of the two components. The infrared energy is instantly absorbed, melting the plastic surface layer. Since the heating element does not touch the material, contamination is eliminated. Once melted, the IR source is withdrawn, and the parts are clamped together.

Key Feature: Speed and cleanliness. Excellent solution for complex, irregularly shaped plastics requiring strong, hermetic seals.

Application: Ideal where high structural integrity and clean joints are paramount, often used in automotive lighting and fluid tanks.

B. Laser Welding (Through-Transmission)

Mechanism: Laser welding is highly precise and involves two components: one that is transmissive to the laser beam (clear or lightly colored) and one that is absorbent (darkly colored). The laser passes through the transmissive part and is absorbed by the second part, generating localized heat at the interface. This heat melts the joining surfaces, and pressure fuses them together.

Key Feature: Creates clean, aesthetically superior joints with minimal flash. Applicable from micro-components to large assemblies due to the use of customized light guides.

C. Overmolding (Integration and Encapsulation)

Mechanism: Unlike joining, overmolding is a primary manufacturing process where a second material (the overmold, often a soft Thermoplastic Elastomer or TPE) is injection molded directly onto a rigid, pre-existing part (the substrate). It is a process of integration, not assembly.

Comparison to Joining: Overmolding doesn’t join two separate pieces; it forms a cohesive unit. This process is inherently durable and custom, improving both function and aesthetics.

Benefits:

Ergonomics: Adding soft, tactile grips (e.g., tool handles).

Protection: Insulating delicate electronics or improving chemical resistance.

Aesthetics: Introducing different colors or textures in a single continuous body.

Vibration Absorption: The TPE acts as a damper for impact and vibration.

2 Simplest Ways of Joining Plastic to Plastic (Chemical and Mechanical)

These foundational methods are still used for their simplicity, low cost, or specific application needs.

A. Solvent Bonding (Chemical Fusion)

Mechanism: Also known as adhesive bonding, this method uses a specialized solvent that temporarily dissolves the surface polymer chains of two compatible plastic pieces. The pieces are pressed together, and the dissolved chains mix and re-solidify (cure) as the solvent slowly evaporates, creating a strong chemical joint.

Key Feature: Simple, low-cost method that avoids heat, making it ideal for thermoplastics sensitive to thermal distortion (where extensive heat could disturb geometry).

Limitation: Requires careful selection of a solvent that is chemically compatible with the specific thermoplastic.

B. Mechanical Fastening (Physical Connection)

Mechanism: This is the least stable but most straightforward joining process, relying on physical elements like screws, bolts, snap-fits, or specialized clips (fasteners) to hold the parts together. This requires the plastic to be hard and strong enough to withstand the insertion and sustained strain of the fastener without cracking.

Key Feature: The resulting connection can be permanent (e.g., plastic rivets) or non-permanent (e.g., screws), making it the best option for products that require repair or disassembly (Design for Disassembly).

Conclusion

The selection of a plastic joining method is a sophisticated trade-off between speed, cost, joint strength, and geometric constraints. Welding methods offer high strength but are limited by material and geometry. Advanced methods like Laser and IR provide precision and cleanliness. Overmolding stands apart by integrating secondary materials and functions directly into the manufacturing step. Ultimately, the choice must align with the specific application requirements, the materials involved, and the necessary production volume.

FAQs

Q1: How does Overmolding differ from Two-Shot (2K) Injection Molding?

A: While both processes involve multiple materials, Overmolding typically uses a sequential approach: the rigid substrate is molded first, removed, and then placed into a second mold where the TPE is injected over it. Two-Shot (2K) Molding, however, keeps the substrate part inside the machine; the mold core rotates, transferring the substrate into a second cavity where the second material is injected, all within one continuous cycle. 2K molding is faster and more precise but requires a significantly more complex and expensive tool.

Q2: Can these welding methods be used to join Dissimilar Plastics?

A: Generally, high-strength welding (Ultrasonic, Vibration, Spin, Hot Plate) works best when joining compatible or identical thermoplastics (e.g., PP to PP, or ABS to PC). Joining two chemically dissimilar plastics (e.g., PP to PVC) usually results in a weak, unreliable joint because the polymer chains cannot properly interdiffuse and fuse. For dissimilar plastics, Solvent Bonding (if chemically compatible) or Mechanical Fastening are often the more reliable assembly methods.

Q3: What is an ‘Energy Director’ and why is it critical in Ultrasonic Welding?

A: An Energy Director is a small, triangular or ridged feature molded directly onto one of the plastic components at the joint interface. Its purpose is threefold: Concentration, Localization, and Initiation. It concentrates the ultrasonic energy into a tiny point, localizes the area where melting should begin, and initiates the frictional melting process extremely quickly. This ensures that the weld occurs rapidly and uniformly along the entire joint line.

Q4: Why is controlling ‘Flash’ important beyond just aesthetics?

A: Flash, the thin layer of plastic squeezed out of the joint during welding or molding, is not just a cosmetic issue. In functional terms, excessive flash can compromise the hermetic sealing of a joint, interfere with the subsequent fit of other parts in an assembly, or create sharp edges that pose a safety risk. It also adds time and cost to the manufacturing process, as it must be manually trimmed or removed in a secondary operation.

Q5: Which joining methods are typically used for Thermoset plastics?

A: Most heat-based welding methods (Ultrasonic, Spin, Hot Plate) are designed for thermoplastics, which can be melted, reshaped, and cooled repeatedly. Thermoset plastics (like phenolics or epoxies) cure irreversibly and cannot be melted. Therefore, thermosets are primarily joined using Solvent/Adhesive Bonding (using epoxy, polyurethane, or similar structural adhesives) or Mechanical Fastening (screws, bolts, inserts), as these methods do not rely on re-melting the base material.